The same “weather” is quite different in purpose and content between general weather, which many people often see every day and which is closely connected to their daily lives, and aviation weather, which is used by certain people as specialized information. In this issue, we spoke with weather professional and Assistant Professor Yuka Fujita of J. F. Oberlin University’s School of Aviation and Management about the differences and content of these two types of weather.

Photo courtesy of Oberlin College

Yuka Fujita

After completing his graduate studies at Rissho University’s Graduate School of Earth and Environmental Sciences, he joined a private weather company. She joined an airline company in 2016 and is in charge of flight operation support operations. He holds certifications as a weather forecaster and flight operations manager, among others.

— What makes aviation weather different from general weather?

First of all, what is the purpose of observation and forecasting? The first question is what is the purpose of observation and forecasting? General meteorological information is provided to protect people’s lives and property from disasters. In addition to disaster prevention information such as warnings and advisories, forecasts are also provided for so-called “life-related” information.

It includes nationwide and weekly weather forecasts, nowcasts (precipitation and high-resolution) of more detailed information using weather radar, and long-span seasonal forecasts (one-month, three-month, warm-weather, and cold-weather) that can be used for agriculture and product sales forecasting.

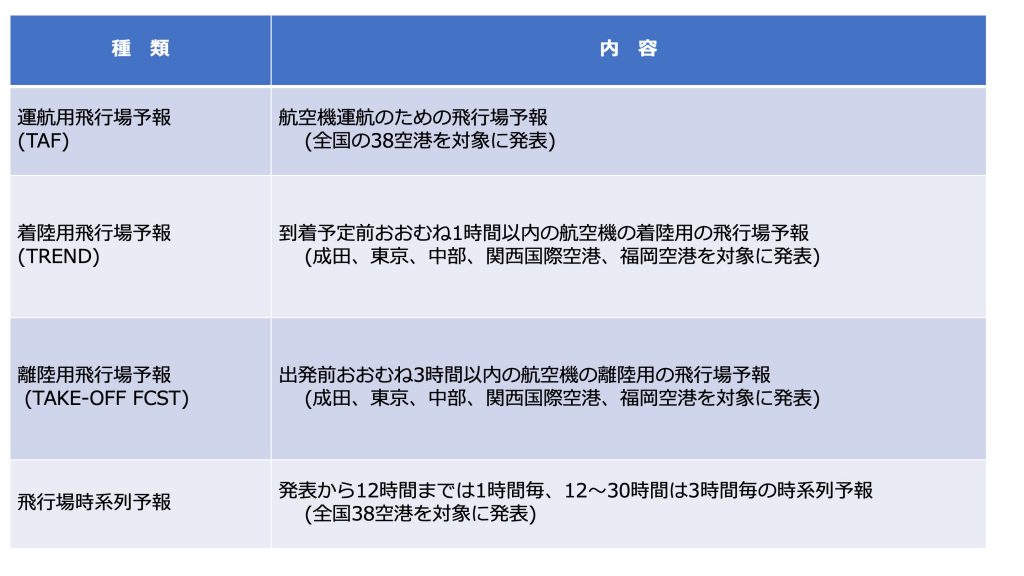

Aviation meteorology is used to prepare flight plans necessary for the safe operation of aircraft, to determine weather conditions at departure and destination airports and airways, and to ensure the safety of aircraft and airport facilities. Unlike general aviation meteorology, the purpose of aviation meteorology is quite specific (specialized), and there are various types of forecasts for this purpose. The table below summarizes all of the forecasts for the airport and its surrounding area, each with different “effective time” and “main purpose”.

Reference: Japan Meteorological Agency

Operational Aerodrome Forecasts (TAF)

Valid up to 30 hours ahead of the announcement, the information is released primarily to assist in flight planning, such as determining weather conditions at departure, destination, alternate airports, etc., and estimating fuel and cargo loading. It is used worldwide and information is exchanged according to internationally established rules.

There are two display formats: telegram and time series. The telegram format, in which the forecast is expressed in numbers and letters, is commonly used. If you are not familiar with this format, you may find it a little confusing. The time-series format is called “airfield time-series forecast (bottom of the table).

Airfield Forecast for Landing (TREND)

It is valid for two hours from the time of the announcement, and as it says “for landing,” it is used for aircraft within approximately one hour prior to scheduled arrival. The TAF is used to provide aircraft in flight with details of changes in the current weather conditions, such as winds that are expected to change from the current conditions at what time and from what minute, and visibility that is expected to decrease. Aircraft in flight fly based on the TAF (above), and the forecast is expressed in terms of “changes within a certain time range. For example, if the forecast changes between 1-4 hours, it may be important to know whether it is before or after the change at the time of landing when that time frame is the scheduled arrival time. For this reason, TREND is published as an addendum to the observed data that pilots use to check weather conditions at their destination. This forecast is only published for the larger airports of Tokyo, Narita, Chubu, Kansai, and Fukuoka.

Takeoff airfield forecast (TAKE OFF FCST)

Valid for 6 hours from announcement and used for aircraft taking off within approximately 3 hours prior to scheduled departure.

The most important difference from other forecasts is that we forecast hourly temperature and pressure. This is because when the temperature is high and the air pressure is low, the density of the air is smaller and the lift obtained is less. For example, if a large amount of cargo is to be loaded, the air temperature and air pressure at takeoff will need to be adjusted accordingly.

Airfield Time Series Forecast

TAF time series format. The TAF is published in two formats: hourly forecasts for the first 12 hours ahead and three-hourly forecasts for the next 12 to 30 hours ahead.

Japan Meteorological Agency (JMA) website, various data and materials > bottom left > aviation weather information > airfield time-series forecast and airfield time-series information

The content of this document is the same as the TAF, but it is more detailed and easier to understand. The content of this document is the same as the TAF, but it is more detailed and easier to understand, so we recommend students who are not yet familiar with the format to view this document as much as possible.

Photo courtesy of Oberlin College

For aviation weather purposes, it is very important to be safe from takeoff to landing. Especially during takeoff and landing, the aircraft is close to the ground surface and flying at low speed, which can be hazardous depending on weather conditions. The most critical landing requires the most attention, and airport observations and forecasts are essential in order to determine if the landing should be redone or if the aircraft should remain in the air if it is unsafe, and to determine if the destination should be changed to a safer airport based on changes in weather conditions and the amount of fuel remaining.

Of course, even during cruising, turbulence and other factors can cause serious injuries (e.g., broken bones) to passengers and flight attendants in the cabin, which could lead to an air accident. When turbulence is detected, the pilot will issue the seatbelt sign and prepare for the turbulence. There are also stages of turbulence intensity, and depending on the intensity encountered, the aircraft may be affected and require inspection.

Thus, by checking weather conditions not only at the airport but also on the route, the aircraft is flying safely.

— In recent years, there has been a lot of focus on “decarbonization” and other aspects of climate change, but does this also affect the aviation weather field?

As the climate changes, there is an undeniable possibility that unprecedented weather phenomena will occur, such as changes in the intensity and location of rainfall. In particular, various studies have been conducted on global warming, and there are reports that the frequency of turbulence will decrease in the Midwest of the North Pacific Ocean, where it occurs frequently today, while it may increase in the surrounding areas. As for snowfall in Japan, some observers believe that the total amount of snowfall will decrease overall during the winter, but that there will be an increase in the number of days of extremely heavy snowfall in a short period of time, such as a heavy snowstorm. When these predictions become reality, it is possible that the airport will not be able to take advantage of its past experience or that the airport will not be able to cope with the situation. For example, if an “unexpected” phenomenon occurs in the drainage capacity of an airport, drainage may not be completed in time, and the runway may be flooded.

impression

— By the way, in 2018, the Kansai International Airport was in trouble due to Typhoon No. 21, wasn’t it?

Yes, the situation was quite serious, with unexpectedly high waves that flooded the airport. It has been reported that the high waves at that time were largely caused by the storm, which was the largest ever recorded in the history of typhoons. It was also reported that last year (2020) at Narita Airport, strong winds caused a parked aircraft to move and contact the bridge, partially damaging it. The effects of strong winds not only affect aircraft in flight, but also those parked on the ground.

There are standards for aircraft to be parked outside, and if the wind speed exceeds those standards, the flight operations department needs to consider such things as loading the aircraft with fuel to make it heavier, putting it in a hangar, or placing it at another safe airport.

Many other things can happen during high winds. When I was with an airline, flying objects could block taxiways and hangar doors could not open. In addition, the topography around airports can cause turbulence at lower levels, which can have a significant impact on aircraft takeoffs and landings. This is my area of research, and I am currently investigating low-level turbulence at Shizuoka Airport.

Thank you very much, Mr. Fujita. In the next interview, we would like to hear from you about your research field and low-level turbulence.

Interviewed by: Yuka Fujita, J. F. Oberlin University (J. F. Oberlin University, School of Aviation and Management)